Thames Valley boroughs face increased housing development by up to 100 per cent if the Government’s new planning proposals are adopted. And this region could be a test case for the country. Bethan Haynes and Daniel Lampard from Lichfields’ Thames Valley office have looked at the possible effects on key council areas in Berkshire, Buckinghamshire and Oxfordshire.

These are exciting times for town planners! Newspaper headlines are dominated by the implications of the Planning for the Future White Paper and the impacts they could have on housing delivery across the Thames Valley and country as a whole.

It’s no surprise that the issue of housing numbers remains a key discussion point and Lichfields work on this has been quoted throughout the national press – continuing the national dialogue about “algorithms” – in this case those governing housing targets.

If adopted, the proposals could mean many authorities facing major increases in housing development.

How did we get here?

The standard method for assessing housing need first appeared in the 2019 NPPF but, after less than two years of being in place, Government has decided that a refresh is needed and some significant changes are proposed.

Perhaps most importantly, the standard method for assessing local housing need is now not the only step in the process. In due course Government is set to publish housing requirements – a second stage where the numbers reflect not only housing but also land supply factors.

What does this mean in the Thames Valley?

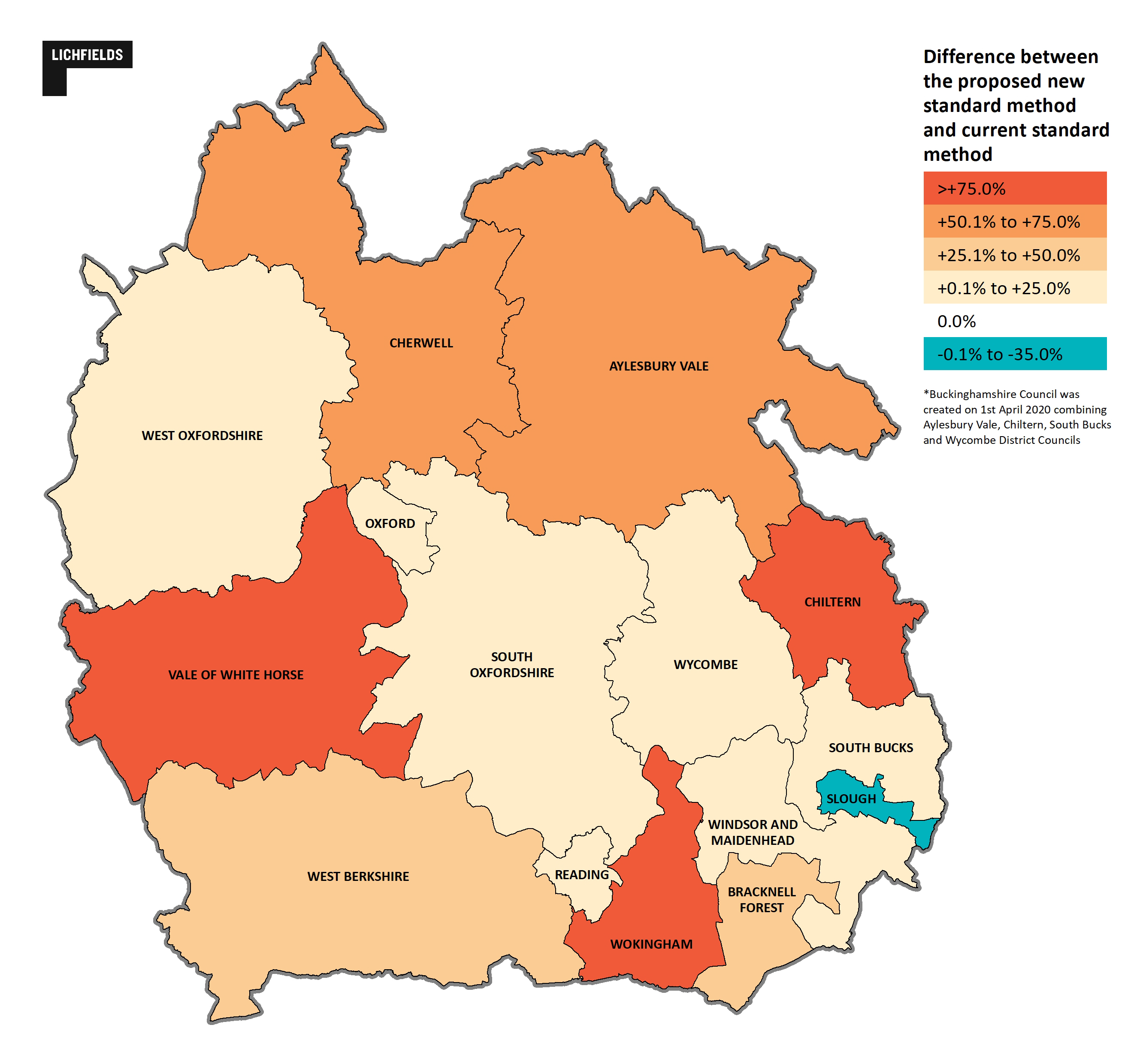

These changes have led to some significant changes in the Thames Valley (see image below which compares the proposed method with the current method. See details of each area here.

On average, the authorities in the Thames Valley have seen their housing affordability ratios increase by 43 per cent in the last 10 years (with Bracknell Forest seeing the highest rise – up 68 per cent) – so it’s easy to see why the increased emphasis on affordability in the proposed method has had a major impact on housing numbers in the region.

As well as more significant affordability uplifts, some authorities have also seen their numbers increase because their baseline has increased.

In Wokingham for example, the baseline is up from 544 to 672 – and that’s before any affordability uplift is applied. The current method created something of a stir locally, with the council seeking a demographic mandate for diverging from the standard method in its emerging plan.

With the proposed method doubling the housing requirement from around 800 to over 1,600 homes per year a strong local reaction is anticipated.

Slough is the only authority to have seen a decrease (to around 600 homes per year), and this is because of the lower baseline.

Although recent housing delivery in Slough has been strong, with an average of around 600 homes a year completed in the last three years (well above the local plan requirement of around 300 per year), with a limited and finite supply of housing land, it is questionable whether Slough can sustain delivery at a level to meet this figure.

The implications of this lower figure on the extent of assistance sought from its neighbours to address unmet housing need are not yet clear. See, for example, the ongoing issue of unmet need in the emerging Chiltern and South Bucks Local Plan.

What about the future?

Despite all of these changes, it’s important to remember that the proposals for the new standard method set out in the planning reform proposals represent only the first part of (what will eventually be) a two-step process.

The proposed method as set out in the proposals generates a figure for local housing need, reflective of stock, household projections and affordability. But, there is an embryonic second part which seeks to address a multitude of other factors; the size of existing urban settlements, the extent of land constraints, brownfield opportunities and demand for other (non-residential) uses.

This would give the housing requirements that local authorities would need to plan for. At the moment, it is for councils to assess to what degree they can meet their need, as far as is consistent with the framework. In effect, Government would take over this task giving authorities an annual housing target which also reflects land supply and constraints.

A simple task? Almost certainly not. There are clearly lots of factors to take into account which need to be carefully balanced and the circumstances in every single local authority in the country are different.

The Thames Valley is likely to be a test case of the difficulties in this balancing exercise. It contains some of the least affordable authorities in the country outside London, and yet many of these areas are almost entirely covered in areas the Government is seeking to protect – Green Belt, Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB), etc.

In Windsor and Maidenhead, for example, house prices are nearly 14 times local incomes, yet the authority is 84 per cent constrained (based on Green Belt and NPPF footnote 6 constraints, rising to 99 per cent once urban land is accounted for).

Similarly, Oxford’s housing pressures are well documented, yet the authority is over 80 per cent urban, and most of what’s left is constrained, meaning overall 98 per cent of land is either constrained or already built on.

In these areas, it remains to be seen whether the number will be kept high as a ‘stick’ to try and ensure councils make the absolute most of all brownfield land, or whether numbers will be redistributed to neighbouring authorities.

At the moment it isn’t clear how the Government will go about this crucial balancing exercise; it seems unlikely that, as currently, some of the relevant factors can simply be totted up in a spreadsheet and applied in a formula – we’ve all seen the controversy around algorithms.

So, how will this be done? Will Government take a more individualistic approach with input from each council (time consuming, but potentially generating the most realistic figures) or will it take a more broad-brush approach (quicker, but with obvious drawbacks)?

And how quickly can it implement all this? We must remember that Government wants every authority to have a plan in place by December 2023.

So, it needs to come up with these housing requirements, and quick. Councils, planners and local residents will no doubt be eagerly awaiting more detail on this next – and arguably crucial – step in the planning process.

Image shows the difference between proposed new standard method and current standard method for local authorities in Thames Valley. Source: Lichfields analysis.

© Thames Tap No 223 (powered by ukpropertyforums.com).

Please rate this article out of five stars below. You can comment too, using the form at the bottom of the page.